Summary:

- Blockchain systems are secured by resources, such as stake or computational power. If the resource’s price goes down, the cost of buying enough resources to attack the system also goes down.

- When an attack’s profit is higher than its cost, then the system becomes (economically) insecure.

- To prevent economic attacks, the system can use alternative resources, whose price does not fluctuate much. These alternative resources can either back special-purpose modules, such as checkpointing, or be used interchangeably with the system’s native resource.

Economic security of blockchain systems is often heralded as the utmost guarantee to strive for. The essence of it is encapsulated by the question: “is the cost of attacking a blockchain system lower than the potential attack profit?”

Answering this question in practice is particularly cumbersome, which is possibly why it is rarely achieved - or discussed - in practice. The main issue is that both the cost and the profit of an attack are often hard to estimate. To make matters worse, the lack of historical attacks is regularly treated as proof of a system’s economic security; “if an attack was profitable, why hasn’t it happened yet?” ask the proponents of this argument. With the introduction of blockchain systems dedicated to particular use cases, such as bridges, and the observation of more sophisticated attacks, the need for proper guarantees, as opposed to heuristics and wishful thinking, is more pressing than ever.

In the cryptographic literature, the economic security question has been most commonly explored in the context of “bootstrapping” newly deployed systems. In this case, the motivation is to protect a system in its infancy, when it has not acquired yet enough capital to secure it, while also enabling it to grow its financial activity. Nonetheless, the question is relevant in all cases when the capital used to secure a blockchain system, i.e., the cost of preventing an attack, is significantly lower than the economic activity hosted on the same system, i.e., the potential profit of an attack.

In this blog post, we explore the most common and well-studied options for enhancing a system’s economic security.

Different assets for different jobs

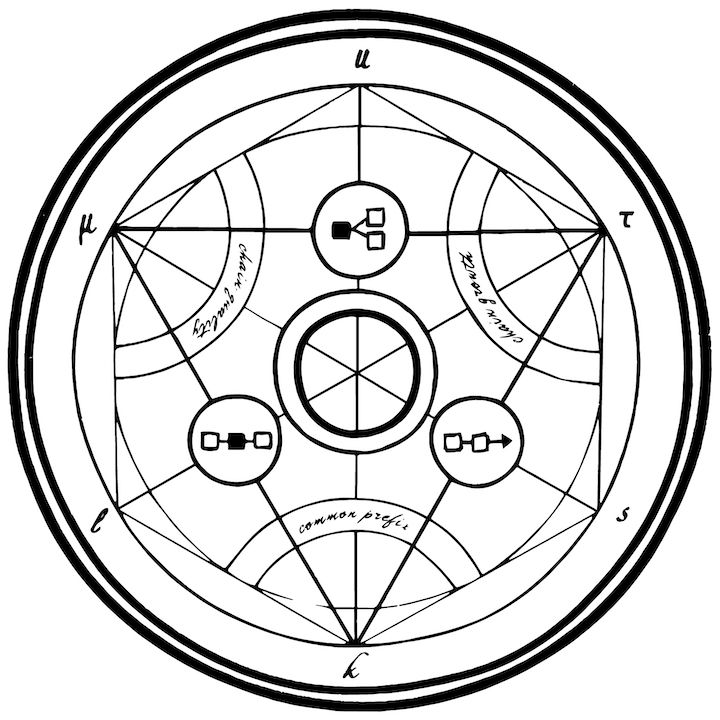

The first approach is to use different resources, such as staking assets, for securing different parts of the system. For example, the parties that control resource A would run the block producing protocol, whereas the parties that control resource B could run a finality gadget for achieving optimistically faster finality (such as GRANDPA1), while resource C would back a committee that enforces slashing, and so on.

In this case, the security of each of the system’s modules is independently backed by a different resource. The main benefit of this approach is that, when the modules are independent, compromising one type of resource could be contained within only the given module. In the above example, if the majority of resource B is adversarially controlled, then the finality gadget would be compromised, so the system would slow down as transactions would be finalized on the (slower) base layer.

However, if the composition of modules is tighter, compromising one could lead to adverse effects in another. Again looking at the above example, if the majority of resource C is maliciously controlled, then the adversary could potentially slash honest parties. In that scenario, honest control over resource A would be reduced, potentially cascading to a compromise of the block production mechanism.

One instance where this approach is used in practice is Babylon. Specifically, Babylon uses both Bitcoin and BABY staking. BABY token holders produce blocks in the Babylon Genesis chain by running a CometBFT protocol instance. Bitcoin stakers act as finality provider, who run a voting protocol that finalizes blocks. Although these two staking processes are seemingly independent, Bitcoin staking is prioritized over BABY staking; for instance, if more than one third of staked Bitcoin fails to participate, then the finalization process - and the whole system - stalls.

Checkpointing

The second approach is a special case of the resource-based job allocation of the first approach. Here the whole system is backed by a single resource, except a single module that periodically checkpoints the system’s state. Checkpoints are unambiguous commitments of the system’s state which cannot be rolled back, preventing chain reorganization or long-range attacks. As long as the checkpointing protocol is secure, checkpoints both are produced on time and are not conflicting.

Checkpointing is a well-known practice that has been extensively studied and used in practice, most often discussed in the context of bootstrapping new systems 2 3 4. There are various ways to implement checkpointing and various resources can be used to support the checkpointing protocol.

Most commonly, checkpointing is run by a committee of parties. These parties collectively sign each checkpoint and, as long as the majority of committee members are honest, checkpoints are correctly issued, meaning both that they are produced on time and that no two checkpoints correspond to conflicting states. The committee members are selected in a permissioned manner, e.g., by centrally choosing a set of designated parties or electing them based on their control of some alternative resource, like stake.

An alternative approach is using an external blockchain to record and organize checkpoints. In this case, the ledger’s state is periodically committed within transactions in the checkpointing blockchain. If the checkpointing blockchain is secure, meaning that it offers safety and liveness guarantees, then the checkpoints are published in an absolute and persistent order. In practice, this approach is also used in Babylon, where the state of the Babylon Genesis chain is periodically published on the Bitcoin blockchain.

The main concern regarding checkpointing is that the system’s security relies solely on the security of the checkpointing module. Specifically, the final choice of the canonical state of the system is made via the issued checkpoints. If the checkpointing module is compromised, e.g., if the checkpointing committee becomes malicious or the checkpointing blockchain is vulnerable, then the system’s security guarantees break down.

Synthetic stake

In both previous approaches the system’s security is eventually dependent on control over a single resource. In the first approach, even if alternative resources are used for securing different parts of the system, the core module is controlled by a single type of resource. Similarly, under checkpointing the final decision regarding the system’s state is made via the checkpoints, which are again controlled by a single resource.

Ideally, we would like to enable the fusion of multiple interchangeable resources, where security is guaranteed if the cumulative power across all resources is honest. Here, different resources are pooled together in a fungible manner to create a “synthetic” (or “virtual”) resource and security is guaranteed as long as the adversary controls a small percentage of the synthetic resources.

Although this approach is particularly appealing, due to its powerful assurances and decentralized nature, it is also the hardest to implement and analyze. Various protocols have been proposed towards this direction, mostly combining computational resources (Proof-of-Work) with digital assets (Proof-of-Stake). For example, in practice, Zano uses a hybrid consensus protocol that combines PoW mining and PoS staking. However, most academic protocols either lack formal guarantees 5 6 or end up prioritizing one over the other 7. Interestingly, a recent promising result presented a concrete protocol that tolerates any adversarial minority over the combined resources 8.

The core complication with synthetic stake is that fusing heterogeneous assets in a fungible manner fundamentally requires a common denomination between all assets. In other words, the system should know the exchange rate of each asset with respect to a common unit of measure. For example, in the case of stake, the common unit of measure is typically USD and the exchange rate is the market price of each token.

The problem is that market prices are not immediately available to a blockchain system, but instead are accessible via oracles. Therefore, the system’s security becomes highly dependent on the oracle’s implementation and trust assumptions. Such oracles are implemented either via a trusted third party, a distributed computing system, or on-chain marketplaces. Each of these options present a tradeoff between high accuracy and centralization.

Conclusion

Increasing economic security of blockchain systems is a pressing problem, particularly when the capital that secures the system is much less than the financial activity conducted on it.

Fortunately various solutions exist, each offering different performance and trust guarantees. First, using different resources for each of the system’s modules can diversify the security capital, as long as these modules are independent and one’s failure is not contagious to the rest of the system. Second, implementing a checkpointing service, which is backed by an alternative resource, is a well-studied and efficient method, albeit the security guarantees essentially move from one resource to another. Third, fusing multiple resources to create synthetic stake is a very promising option for increasing economic security in a decentralized manner. Nonetheless, properly designing and implementing an on-chain price oracle for each resource is a delicate process that, if done incorrectly, may introduce unforeseen hazards or centralization tendencies.

Regardless of which option one chooses though, a designer’s first step should always be to understand their own system’s particularities. Once they define how their system’s modules cooperate, which trust and centralization compromises they can tolerate, and what level of performance they strive for, choosing an appropriate solution should become straightforward.

References

- Stewart, Alistair, and Eleftherios Kokoris-Kogia. “Grandpa: a byzantine finality gadget.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2007.01560 (2020); arXiv 2007.01560

- Rana, Ranvir, et al. “Optimal bootstrapping of pow blockchains.” Proceedings of the Twenty-Third International Symposium on Theory, Algorithmic Foundations, and Protocol Design for Mobile Networks and Mobile Computing. 2022; arxiv 2208.10618

- Karakostas, Dimitris, and Aggelos Kiayias. “Securing proof-of-work ledgers via checkpointing.” 2021 IEEE International Conference on Blockchain and Cryptocurrency (ICBC). IEEE, 2021; eprint 2020 / 173

- Dinsdale-Young, Thomas, et al. “Afgjort: A partially synchronous finality layer for blockchains.” International Conference on Security and Cryptography for Networks. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2020; eprint 2019 / 504

- Bentov, Iddo, et al. “Proof of activity: Extending bitcoin’s proof of work via proof of stake [Extended abstract].” ACM SIGMETRICS Performance Evaluation Review 42.3 (2014): 34-37; DOI 10.1145 / 2695533.2695545

- Duong, Tuyet, et al. “Twinscoin: A cryptocurrency via proof-of-work and proof-of-stake.” Proceedings of the 2nd ACM Workshop on Blockchains, Cryptocurrencies, and Contracts. 2018; DOI 10.1145 / 3205230.3205233

- Duong, Tuyet, et al. “2-hop blockchain: combining proof-of-work and proof-of-stake securely.” European Symposium on Research in Computer Security. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2020; eprint 2016 / 716

- Fitzi, Matthias, et al. “Minotaur: Multi-resource blockchain consensus.” Proceedings of the 2022 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security. 2022; DOI 10.1145 / 3548606.3559356